Lemon, hammerhead and tiger sharks frequently migrate over distances of several 1,000 km in the Bahamas/Florida region. On their migrations, they pass through areas where they are not protected.

Great hammerhead shark (Sphyrna mokarran).

Photo © Shutterstock

Background

Between 2007 and 2015, the Foundation supported the project of Prof. Samuel "Doc" Gruber and Steve Kessel Lemon sharks in Jupiter/FL. Towards the end of the project, it became clear that not only lemon sharks but also other large sharks such as hammerheads and tiger sharks undergo large migrations in the region. During their migrations, which are often up to 3,000 km long, the sharks pass through areas where they are not protected or not sufficiently protected.

In 2015, the Jupiter project was terminated and the project "Migrations of large shark species in the Bahamas and Florida region" was launched, with large hammerhead sharks (Sphyrna mokarran) being the initial focus. However, lemon sharks and tiger sharks will also be studied in the process, if they are caught.

Hammerheads are often found in the bycatch, but are also actively fished because their fins command a high market value. Regulating bycatch and requiring hammerhead sharks to be thrown back into the sea makes little sense, as the mortality of hammerhead sharks in bycatch is the highest of all species at about 90%. For this reason, the whereabouts, seasonal space usage, and behavior of these hammerhead shark species need to be much better understood in order to protect them more effectively.

Great hammerhead sharks were added to both Appendix II of the CITES Convention and the IUCN Red List as Endangered in March 2014. They migrate globally over long distances through the territories of different nations. For this reason, they are also included in Annex I of the UN Convention on the Conservation of Highly Migratory Species (CMS), which calls for strong cooperation among all participating nations in the management of these species.

Goal

The long-term goal of the project is to provide scientifically sound data to the U.S. National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS) to place great hammerhead sharks and, where appropriate, other large sharks under protection in the U.S. exclusive national fishing zone (EEZ, or the Exclusive Economic Zones).

Because of their extremely high mortality rate on board, hammerhead sharks must be prevented from being caught at all be it commercially or by so-called "sport" fishermen.

Methods

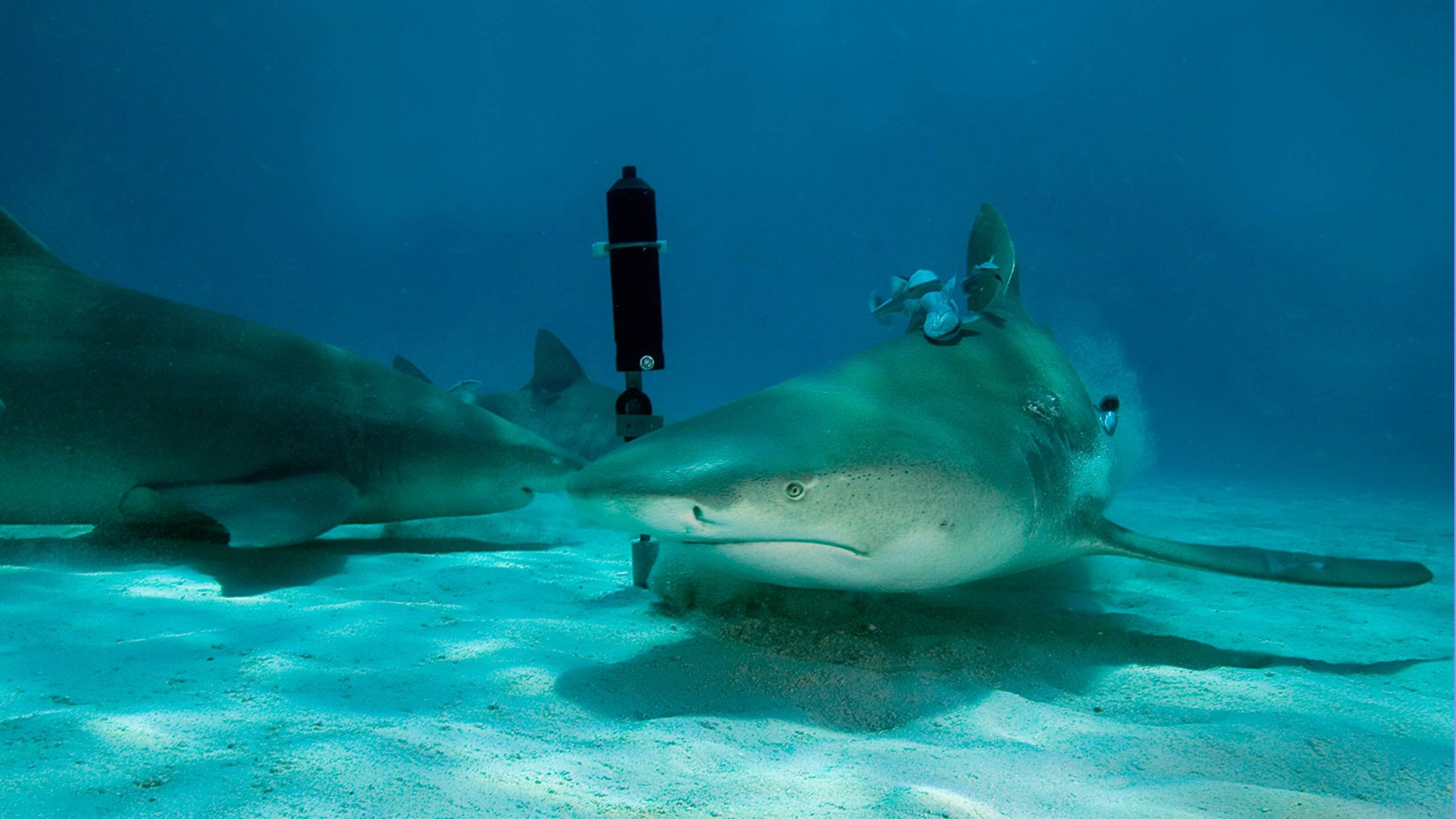

- The sharks are caught with bait. With its many years of field experience, the team is able to perform the necessary examination on the sharks within less than 10 minutes. This guarantees a very high probability of survival, even for the especially sensitive hammerhead sharks.

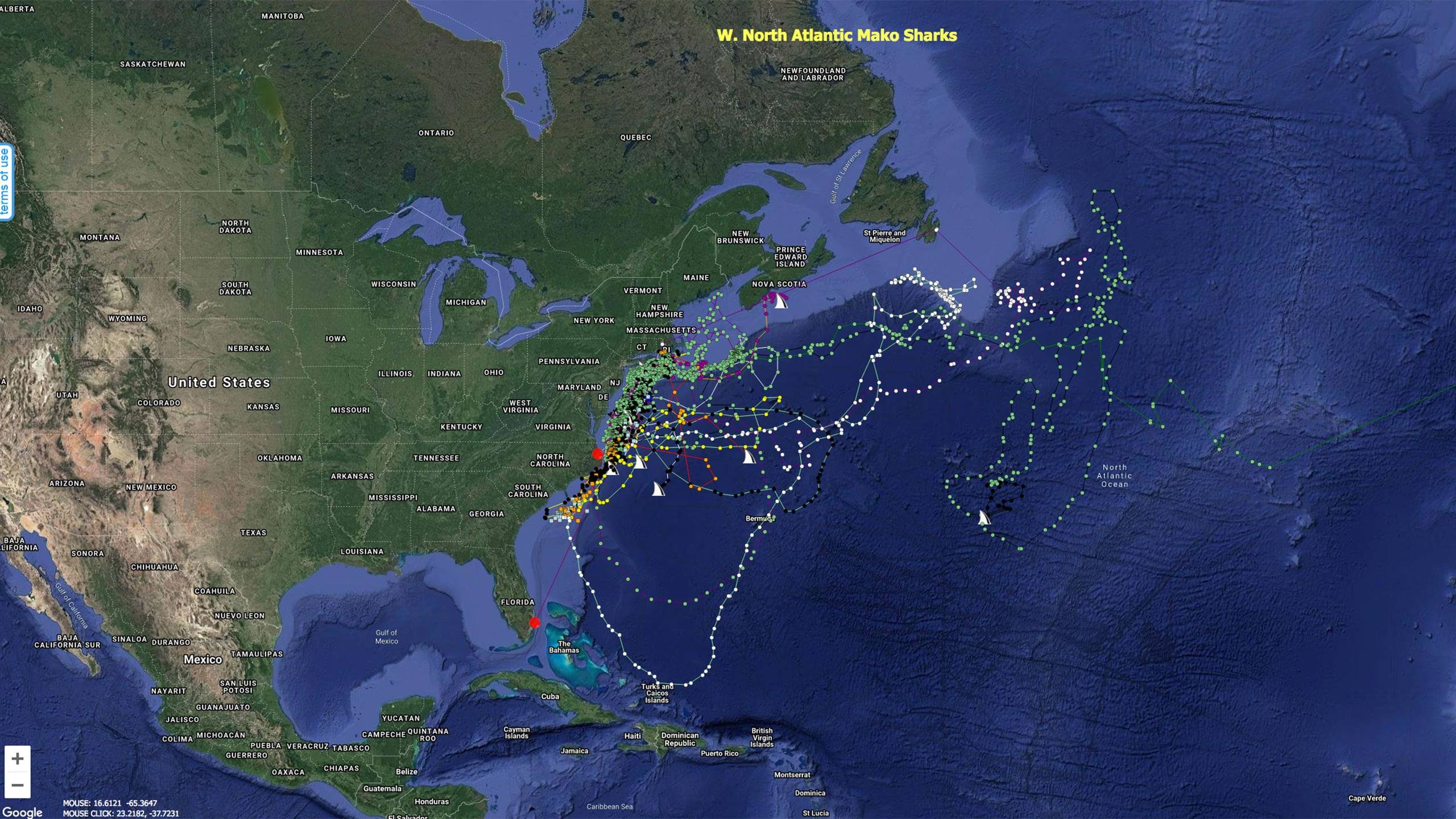

- Collection of data on the seasonal large- and small-scale migrations of great sharks in the Florida/Bahamas regions. Satellite and acoustic transmitters as well as classical tags and photo-identification will be used for this purpose.

- Food habits will be determined using stable isotope analysis.

- Ultrasound and hormone examinations will provide clues to potential nurseries and parturition sites.

Results

Analyses of the movements of great hammerhead sharks confirm philopatric (breeding site fidelity) behavior. They migrate in annual cycles, staying seasonally in one location and maintaining this behavior for years. In Bimini and the Bahamas, they stay from October to April, and in Jupiter/Florida from October to March. Hammerhead sharks equipped with satellite transmitters in Bimini or Jupiter migrated to Northern Virginia and back, a total distance of about 3,000 km. Such seasonal and thus predictable migrations are dangerous for the already severely threatened hammerhead shark populations. They increase the likelihood that they will be targeted or die in bycatch.

Based on scientific data on the migrations and ranges of lemon sharks and great hammerhead sharks, a request was made in 2016 to the U.S. National Marine Fisheries Service (NOAA-NMFS) to expand protection zones and seasons for these sharks. In the region between Cape Canaveral and Palm Beach, the protected EFH zone (Essential Fish Habitat), in which the sharks may not be caught year-round, will be extended to 245 km. Unfortunately, regarding the start date of the shark fishing in the other regions in January - requested was July - only a compromise with NMFS could be reached. If the first 20% of the lemon shark catch quota is reached too early, the remaining 80% will not be released until July.

In a collaborative effort with Dr. Natalie Mylnicenko (Disney Science and Environment), Great Hammerhead females were screened for pregnancy using portable ultrasound equipment. One female was pregnant and was fitted with a satellite transmitter. She left Bimini in late May and her transmitter surfaced 30 km off the Georgia coast in July. Since newborn great hammerhead sharks have recently been found further northeast in South Carolina, it is likely that the female was in Bimini during her gestation period and then swam to South Carolina to give birth. It is particularly critical for species conservation when pregnant females leave the Bimini shark sanctuary and cross unprotected U.S. waters during this very important period.

In 2017, a scientific publication was published on the results and they were also presented at the American Elasmobranch Society conference in Austin.

To date, the data have been published in four scientific articles and presented at the annual meetings of the American Elasmobranch Society.

Project Status

The project got off to a good start. However, after the death of Samuel Gruber in April 2019 and due to the 2020/2021 Covid pandemic, it fell severely behind schedule. In early 2020, the project was taken over by Matt Smukall, CEO of the Shark Lab in Bimini.

Administrative Details

Project status: in progress since 2015

Project Management: Matt Smukall (earlier Samuel Gruber, Steve Kessel).

Funding: 2020 CHF 18,700.

Funding since 2015: CHF 86,200.