Shark habitats

70.8% of the earth's surface is covered by water. The oceans contain around 96% of the earth's total water supply, or over 1.332 billion cubic kilometers. But not all seas are the same. The largest biodiversity and thus the largest food supply are found in the relatively shallow waters above the shelf areas off the coasts - which are only about 200 m deep. There the rivers carry nutrients into the water for microorganisms, which form the basis of all food webs. Most of the approximately 500 known shark species live in these biologically highly productive areas. However, sharks have also conquered the high seas and the deep sea and some even live in fresh water.

But the oceans are not an easy place to live. High salinity, poor visibility up to eternal night, large pressure differences, huge expanses and low temperatures require specific adaptations.

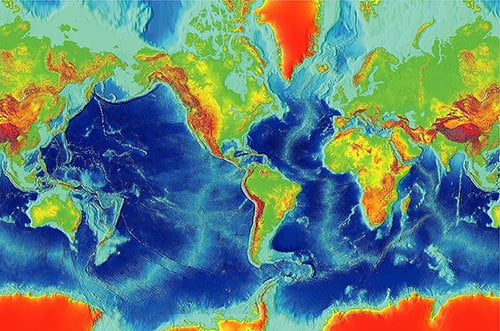

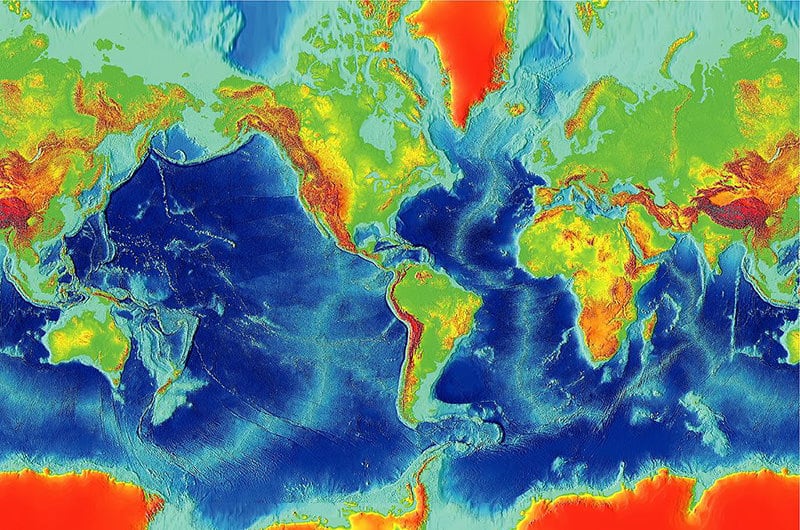

The shelf regions are shown in a bright turquoise in this picture.

Photo © NOAA

Photo © Alexa Elliot

Adaptations to life in the water

Waterworld

The sea is a complex, three-dimensional habitat. Life in the water is not easy and requires specific adaptations from all organisms living there.

Body shapes

The habitat and the way of life also determine the body shape in the sea. The bodies of the fast swimming sharks are usually torpedo shaped. Bottom-dwelling forms are usually more flat and have broad pectoral fins. The most bizarre sharks are found in the deep sea, although so far there is no clear explanation for many of their special adaptations.

Visibility and vision

Visibility under water is usually much worse than on land. Water contains suspended particles and absorbs light. If you want to see under water, you practically need a night vision device.

Odours and sense of smell

To smell something in the sea, one must have a very good nose. Smells spread much more slowly in water than in the air.

Sound and hearing

Anyone with poor vision must be able to hear well. Sound spreads faster in water than on land because of its high density. Sharks locate distant prey with their ears.

Orientation

Orientation under water is very difficult, especially in the open sea. In the absence of landmarks, sharks become a compass. The earth's magnetic fields help them to orient themselves. How they do this is still largely unexplored.

Pressure and water density

Swimming under water is quite easy, provided you have the right buoyancy and systems for pressure equalization. Sharks do not have a swim bladder and usually use their very large, oil-rich liver as a buoyancy device.

Salinity

Without sophisticated regulation of the body's own salt and water balance, sharks would be spherical, because the salt content of their body is higher than that of the surrounding seawater and therefore attracts water.

Respiration

In the sea the oxygen must be wrested from the water. In cartilaginous and bony fish this is done by means of gills. But the cold sea water permanently flows through the gills and withdraws heat from the body.

Temperature

Any animal whose temperature is a few degrees warmer than others is both faster and a more efficient hunter. The law of heat says that an increase of 10 degrees Celsius doubles or triples the speed of a chemical reaction. Some shark species can maintain their body temperature well above water temperature.

Photo © Shutterstock

High seas: The deserts of the seas

The high seas are the deserts of the oceans. They are infinite three-dimensional expanses with little food, because the food chains are based on microorganisms which in turn depend on minerals carried into the sea by rivers or brought to the surface by deep ocean currents. However, there are also some oases where rich life exists and where food chains can develop, as for example in the Sargasso Sea.

The food chains in the sea are complex and the availability of sufficient food often depends on the seasons. Plankton is the basis of all life. However, plankton blooms only occur at certain times and places. Plankton-eating sharks such as whale sharks and basking sharks migrate from plankton bloom to plankton bloom. But sharks that feed on fish also frequent these regions because during plankton blooms, the smallest up to the largest of fish gather there. Sharks often travel enormous distances in search of food, which can amount to several 1,000 km per year.

Deep-sea sharks such as makos and blue sharks also follow fish shoals in search of food. This leads them into the fishing grounds of international fishing fleets where they are brutally decimated. Long migration routes also make them difficult to protect. If an endangered shark species is protected in one country, it may well be that it pass through regions where they find no protection. This is where the Convention on Migratory Species (CMS) attempts to coordinate the countries.

Photo © BPA

Deep sea: eternal night, freezing cold and extreme pressure conditions

The deep sea is probably the most inhospitable region on earth. The eternal night of the deep sea makes visibility and navigation difficult and demands extreme adaptations on the part of its inhabitants. Temperatures there are usually 4° Celsius and this makes for the heaviest water. The pressure conditions of several hundred atmospheres even affect biological and biochemical processes.

But here too, sharks have propagated and developed the most bizarre forms. The goblin shark with its long nose and very long, pointed teeth is only one of these forms.

Lantern sharks, which also inhabit the deep sea, got their name from the fact that they glow in the dark. Their specific light patterns are intended to help them identify their species.

Photo © Steve de Neef

Shelf regions: The land of milk and honey

The continental shelves with their reefs, tidal flats, sand and rock structures represent the most complex marine habitat. Rivers bring nutrient-rich water to the sea and always supply the lowest links in the food chain with sufficient minerals and nutrients. This is how large, complex food webs can develop. The highly structured habitat offers various ecological niches that favour a great diversity of species.

Coral reefs are formed in regions with exactly the right temperature, sufficient nutrients and at depths where there is still sufficient light. The species richness of the reefs is enormous; they offer hunting grounds and hiding places for many species of worms, shells, crabs and fish. Sharks – from the bottom-dwelling species specialized in mussels and crabs to pure reef sharks – also attract deep-sea sharks with their food supply.

But many reefs, such as the Great Barrier Reef off the coast of Australia, are endangered by pollution, global warming and acidification of the oceans due to too much carbon dioxide.

Photo © Klaus Jost

Fresh water

A few sharks and rays can live temporarily in freshwater or brackish water.

Only a few species like the bull sharks spend longer periods in freshwater. Bull sharks are often found in river mouths, but can also swim up rivers for thousands of kilometers, e.g. in the Amazon, or appear in lakes. In Fiji, juvenile bull sharks can be found in river courses protected from larger marine hunters. In Lake Nicaragua, an entire bull shark population exists or has existed, having spent its entire life in the lake, never returning to the sea (landlocked). This is the only known population of bull sharks living in a lake, but it seems to have been wiped out by fishermen, as documented by a French camera team who apparently found no bull sharks in Lake Nicaragua a few years ago.

Some shark species live effectively in freshwater. These include the sharks of the genus Glyphis found in rivers like the Ganges and Hugli in India, West Bengal and possibly Pakistan. On the IUCN Red List, Ganges sharks are classified as critically endangered. It is questionable whether they even still exist.

Photo © Charlotte Sams

Mangrove areas: The protected nurseries

The mangrove areas of the tropical and subtropical regions are used by fish and sharks as nurseries. These shallow water regions are difficult to access for larger hunters. The mangrove roots offer protection and young animals find a rich food supply between them.